Chapter 1: Background, Exposition, Setting

“Today we are going to work on the organization of our stories. I know that your regular teacher has been working with you for two weeks on your stories and after looking through your notebooks, I realized that while they are all good stories, they all need some work on organization to make them great.

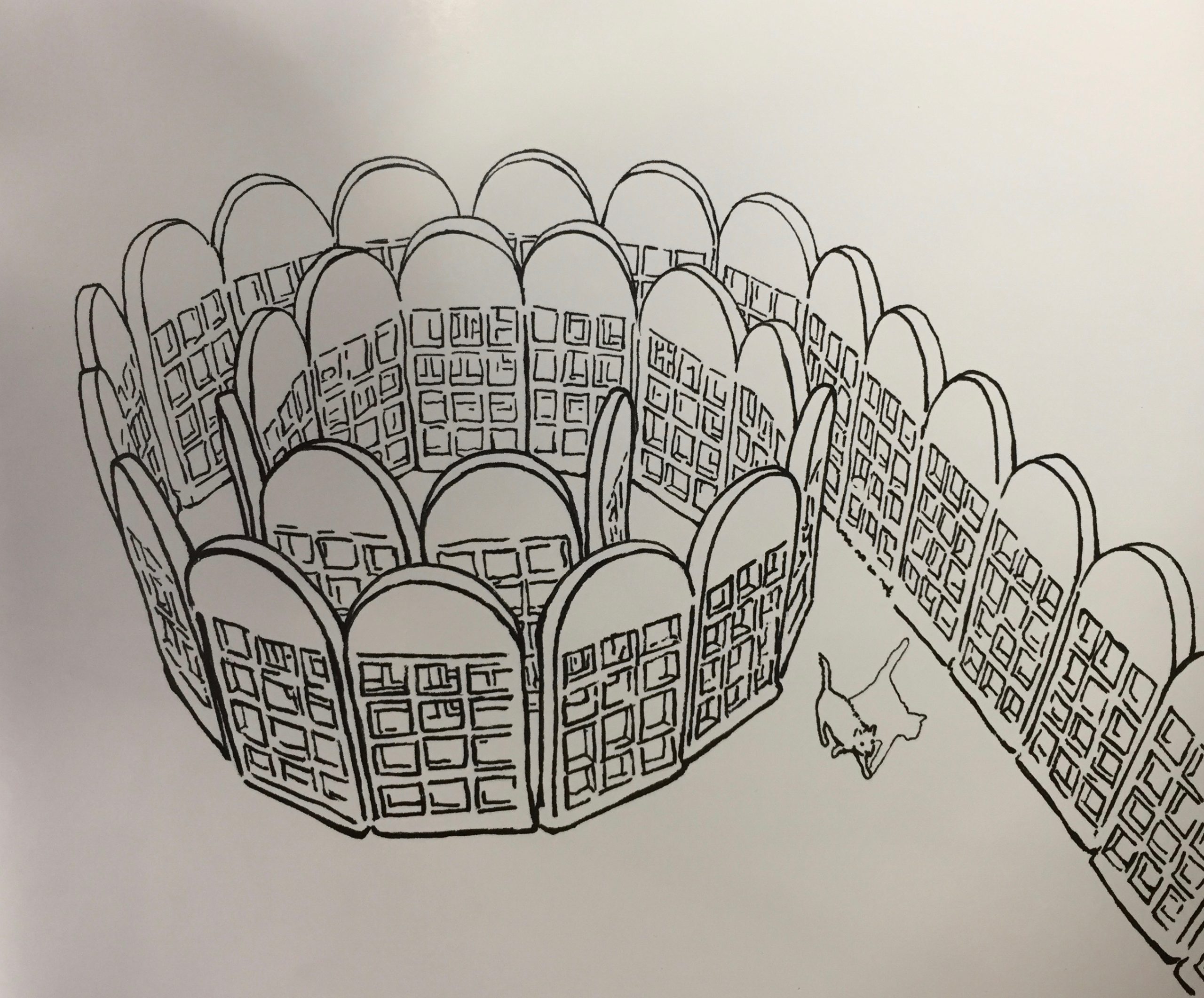

“Now, how many of you have ever seen this?” I ask, indicating a depiction I have put on the whiteboard of Freytag’s Pyramid. A few scattered hands, among the 22 4th grade students I am substitute-teaching, raise.

“Well, as you may remember, there are a few major parts to a story, the background (also known as exposition or setting), rising action, climax, and finally the resolution. Today we are going to concentrate on the climax, which is often the most exciting part of a story.

“The climax is often considered the main event of a story. It is the major bit of action that the whole story has been building to.

“Who can tell me what a ‘spoiler’ is?”

I call on Warren’s silent hand: “It’s like… when somebody tells you what happens at the end of a movie?”

“Yeah, exactly. So do we think that the climax, which usually comes at the end of a story, and is the most important part, could be related to the spoiler? And if so, how?”

I call on Lenny: “Well… Well… they are probably related… because… if I tell you the climax of a story then that would probably be a spoiler?”

“Exactly! If you give away that most exciting piece of the story too soon, the story is kinda spoiled, because now the reader knows how it will end and they aren’t as excited to continue reading.

“Now, how many of you like baseball?” nearly every hand shoots up. “And who can tell me what just happened in Major League Baseball?”

“The Giants won the World Series!” more than half the class shouts.

“Silent hands please. Yes, the Giants won the World Series, and what part of our pyramid do you think that win would be? Setting, rising action, climax, or resolution?”

Joshua’s hand shoots up. “Yes, Joshua?”

“The climax?” he says hesitantly.

“Yes, be confident Joshua! Yes, that would be the climax. Since everyone is doing true stories about themselves, let’s use the ‘story’ of this season’s Giants to help us understand timing in our own stories.

Now, we all know the Giants won it all, but if we are writing this story for someone who doesn’t know, where do you think we should start if we wanted a long story and where would we start if we wanted a short story?”

Nick raises his hand for the first time: “A long story might start at opening day. And a short one might…”

Eddy interrupts: “Start at the beginning of the World Series!”

“Eddy, Nick had the floor.”

“Yeah, or maybe the beginning of the playoffs?” Nick offers.

“Good. All good answers. And while we are telling all the details of the story, would we want to mention on page one that ‘at the end of this year, the Giants will win the World Series when The Panda Catches a fly ball for the third out of game seven against the Royals?”

“No!” the class shouts.

“Silent hands please. But that’s correct. And why not?”

Chris raises his hand: “Because then there wouldn’t be a point to reading the story.”

“Right, in other words that is the climax and telling it too early would…

“Would do what to the ending…?

“We just talked about it…”

Joshua again: “Spoil it?”

“Yes, Joshua. Good.

“Now, your writing notebooks are on your desks. What I want you all to do is walk quietly to your desks and take a seat. At your desks, I want you to read through your stories to refresh yourselves after the long weekend. Then I want each of you to put a star next to the climax of your story. When you have done that, raise your hands and I will come around and check everyone. And while you wait for me to come around, make sure that your climax comes at the end of the story and make sure that you don’t give away the ending in the early pages of your story. Alright, go ahead.”

Chapter 2: Rising action

As I walk the classroom, most of the students are vaguely on target with their stories. Jesse has 6 pages on a time he scored a basket in a basketball game. He knows that he needs to emphasize the challenges he faced in scoring his basket. He knows that he needs to help the audience understand how and why this one basket, scored by him during a blowout that his team was on the losing end of, was such a powerful moment that he should memorialize it in an autobiographical story. He has it figured, once I explain the ways he needs to offer an explanation of his own abilities and the immense skill of his opponents. He must meticulously articulate his peculiar experience in order for the readers to appreciate the gravity of the experience. Unless Jesse empowers readers to empathize with him, those readers will have little interest in an apparently meaningless garbage-time basket scored in a regular-season loss.

Lenny has 5 pages of a story about the construction site that he goes to with his father where they play among rubble and sand piles, moving sand and debris from one part of the jobsite to another. Lenny needs to decide what his climax is going to be, and how there will be a resolution to his piece of raw, 4th grade realism.

“Have there been any challenges in your work?”

“Sometimes we go after it rains and our sand piles have been washed away…”

“Great, I would love for you to talk about that in the early parts. And do you have a vision for a finished product or an endpoint of your work? What do you imagine it will look like when you are done? Can you describe the final vision to the reader?”

He understands that he needs another page or two to explain his enthusiasm for the project and his aspirations for this debris-moving exercise. He sees that he must explain more clearly the challenges of coming back after a rain to find that his debris pile has been eroded. He must expand this rising action by adding complications, and that can ultimately culminate in a desire to see the project achieve his vision. The complications will give the reader an understanding of his renewed dedication and finishing a hard session of work off with a description of his vision will round out the story and give a sense of resolution.

Noah’s hand is raised. I walk to Noah’s desk.

“What can I do for you Noah?”

“I’m done.”

Oh boy. “Oh yeah? Well why don’t I take a look at your story to make sure?”

“Ok.”

Noah’s story deals with the time Noah’s dad took him mountain biking. The climax being that Noah fell. I know because the fall at the end is starred and because it is the only thing that happens in the story. I also know because he tells readers in paragraph one that he is going to fall at the end of the story.

Noah’s “done” story is a page-and-a-half. In that space he repeatedly informs readers that in the end he will fall but that it won’t be so bad. He tells readers this information three times on page one. In loosely shrouded language he reminds readers several times, on the first page, that ultimately he is going to fall off of his bike. Do you get the point yet? In case you don’t:

The first time, he apparently records this information just because.

Shortly thereafter, Noah’s dad is explaining the dangers of mountain biking and explaining strategies that will keep Noah from crashing. This would be a nice bit of foreshadowing except immediately following the current piece of dialogue with his father, Noah again reminds readers that he is going to fall off of his bike on page two and, again, this is already the second reminder of the fall.

Then Noah briefly describes the mountain, specifically a narrow portion of the trail, and immediately thereafter reminds readers that he is going to fall on this exact section of trail.

Noah falls.

It happens so fast and amidst so much hype that I almost miss it when it does happen. Perhaps he figured he had already told readers it was going to happen so he didn’t need to drag it out?

Then the story is over.

Good grief does this need some work. What has he been doing with his real teacher for the last two weeks? “I really like what you’ve done here bud, but I think there is some re-arranging you could do, and also some details you might add to really give your readers a better understanding of why this was important. It would also help readers understand more about what this experience was like for you.

“So, first, I think you should move all the pieces about your crash to one place. Move them here, to the end. I like the details of the crash, but I think that since that is the main event of the story, the climax, like we were just discussing, since that is the climax, I think you shouldn’t spoil it by talking about it too soon.

“So can you move those parts, then maybe add even more details about the crash?”

“Ok.”

“Great, and once you are done, raise your hand and I’ll come check in again.”

“Ok.”

I walk around the room for a minute or two, monitoring other students’ progress.

Noah raises his hand again.

Oh jeeze. “You get that done bud?”

“Yeah”

“Alright, let me check it out.” Looking at his notebook, Noah has drawn arrows indicating the proper re-location sites for a few sentences and has erased a word here and there.

He has not added a single word to his story. “Ok, good. I like that you pulled those pieces to the end, but can you add some more details for me?” Please? Do something?

“But this happened a long time ago… so I don’t rrrreally remember details.”

You’re 11. “Ok, well have you been to Petaluma other times?”

“Yeah”

This was like 6 months ago. “So you could write about the drive a little. Did you drive?”

“Yeah. But it was a long time ago.”

None of your personal life experiences happened a long time ago. “Ok, well what season was it?”

“I don’t remember. And it doesn’t fit.”

Remember how you are 11? You should remember your whole life at 11. And if this is not memorable enough to log in your 11 expansive years of memories, why are you writing about it? “Ok, well did you and your dad talk on the drive? Because, you knowwww, authors will often fill in dialogue by using common conversations instead of the specific conversation that happened at the time of the story. Even great authors don’t usually have a recording of a conversation, which means they probably don’t remember whole conversations either. So, to lend a bit of realism to their story, they will write in dialogue that might normally have happened in that situation. Like a conversation type they often have with the person they are talking to at that moment in the story.

“So, is there anything that you and your dad talk about often? Like sports? Maybe about the Giants?”

“I don’t like baseball.”

The only boy in San Francisco who hates the Giants two weeks after they won the World friggin’ Series. “Well is there a sport you do like? One that you and your dad talk about? Football? Basketball?”

“No.”

Mentally pulling my hair out. “You don’t play any sports?”

“Oh yeah, I like to play lacrosse.”

You little… booger. “Ok, well maybe you and your dad could be talking about lacrosse on the drive to Petaluma?”

“Mayyyybe.”

Chapter 3: Climax

“Maybe you could be talking to your dad about a game of lacrosse you played? Or about a nice play you made, maybe even a goal you scored?”

“It doesn’t fit.”

It doesn’t fit? It doesn’t fit?!?! Your story is one page long, has no climax, and you swear you’re done. Make it fit! You can’t have a story about nothing that is 5 pages shorter than the rest of the class! “Well, if you have that in the beginning of the story, then readers will start to learn about you. They will learn that you play lacrosse and then they will infer things. Maybe they will think to themselves: ‘hey, Noah scored that goal in lacrosse, he must have good balance.’

“Remember that example we went over earlier? how readers learn other information from what is said in a story beyond simply the words? Like, since the person in the example had to drive on the freeway to get to Pacifica, we inferred that the person lived a pretty long ways away and we inferred that the person probably had a license and was old enough to drive. That’s the same effect you want to create for your story. You want the reader to learn about you and begin to understand you a little bit as the story goes along.

“And for your story it will make the ending that much more of a surprise. The reader will find out that you lost your balance and crashed while riding your bike after inferring that you have good balance, so they will have learned about you and been surprised when their expectations and assumptions were turned upside down.” Like you on that bike.

“I guess I can try that.”

Chapter 4: Resolution

Apparently even Freytag’s Great Pyramid can’t make me a good writer. Forget what you just read. I’m a bad teacher. Sorry.