Like the scholar Andreas Huyssen, I like to think of cities as texts to be read. That little happens frantically in Ghana would be a parenthetical the the text of the country. A longer passage is due to the Cape Coast Castle.

The Cape Coast Castle once featured active canons. Prisoners were kept in the dungeons until ships bore them across the Atlantic Ocean and into slavery. An artifact of European imperialism and slavery, the castle now functions as a museum. The Ghanaian scholar Kwame Appiah addresses museums and culture in the book Whose Culture is it? where he writes: “I actually want museums in Europe to be able to show the riches of the society they plundered…” (84). An emblem of that plunder occupies what might be expensive coastal real estate. The aura of the castle, like the trauma it represents, looms imposing and brutal over the picturesque landscape.

That the castle’s aura can affect the curious, even in narrative form, is this essay’s assumption. So, tie your shoes.

You arrive in Cape Coast by trotro, a van that operates like an on-demand bus. From the trotro station, you catch a taxi to the accommodations you booked. Called Oasis Beach Resort, it is located on the beach and it has several cabanas. The thatch-roof structures with tables and chairs direct your gaze towards the Atlantic Ocean. The Oasis’s amenities barely rival a Motel 6, though the beachfront location is spectacular. Big, stormy waves roll onto the white-gray sand. There are only two other groups at the resort and most of them avoid swimming in the ocean.

You arrive in Cape Coast by trotro, a van that operates like an on-demand bus. From the trotro station, you catch a taxi to the accommodations you booked. Called Oasis Beach Resort, it is located on the beach and it has several cabanas. The thatch-roof structures with tables and chairs direct your gaze towards the Atlantic Ocean. The Oasis’s amenities barely rival a Motel 6, though the beachfront location is spectacular. Big, stormy waves roll onto the white-gray sand. There are only two other groups at the resort and most of them avoid swimming in the ocean.

The primary reason to stay at the Oasis, and seemingly to stay in Cape Coast, is to visit Cape Coast Castle. It’s summer. You sit in the cabanas while your traveling partner gets ready. You have a beer while you wait. It’s sunny out. Summer in Ghana brings rain in fits, even at the beach. But it’s sunny for the moment, even if it may rain soon. The weather swings between poles, reflecting the schism of a beautiful beach in the shadow of a slave castle.

When rain comes, it comes hard and heavy, but it doesn’t stay long. You wish your partner would hurry, because you won’t go to the castle if it’s raining. You don’t want to be soaking wet on a museum tour.

Your partner emerges and you decided to walk up the hill to the castle on a bluff overlooking the sea. Bright sunlight reflects off the sand and off the whitewashed walls of the resort. The glaring walls are only broken by the Ghanaian symbol painted here and there on the outside of the white buildings. The symbol is like a fossil Pokémon. Fish bones in the center with two tails 180 degrees across from one another trailing off the bones and encircling them in opposite directions, each ending at the start of the other. Like an Ashanti yin-yang of fish bones. The ‘bones’ are stylized, cartoonish. Pokémon. Not menacing. But bones. The symbol means “except for God.” The symbol’s prevalence ties it to the Ghanaian greeting “akwaba,” which means “you are welcome,” which is also omni-present. And you think about these symbols as you walk to Cape Coast Castle.

You wear sunglasses because it’s so sunny and the castle is whitewashed too and your eyes hurt walking around with all that sunlight everywhere bouncing off the white things (that aren’t white under the paint). The sunlight seems like it ought to be happy, warm. For now, it is. You take pictures on the walk of old buildings or the novelties of a landscape that seems healthy against buildings slowly, casually crumbling.

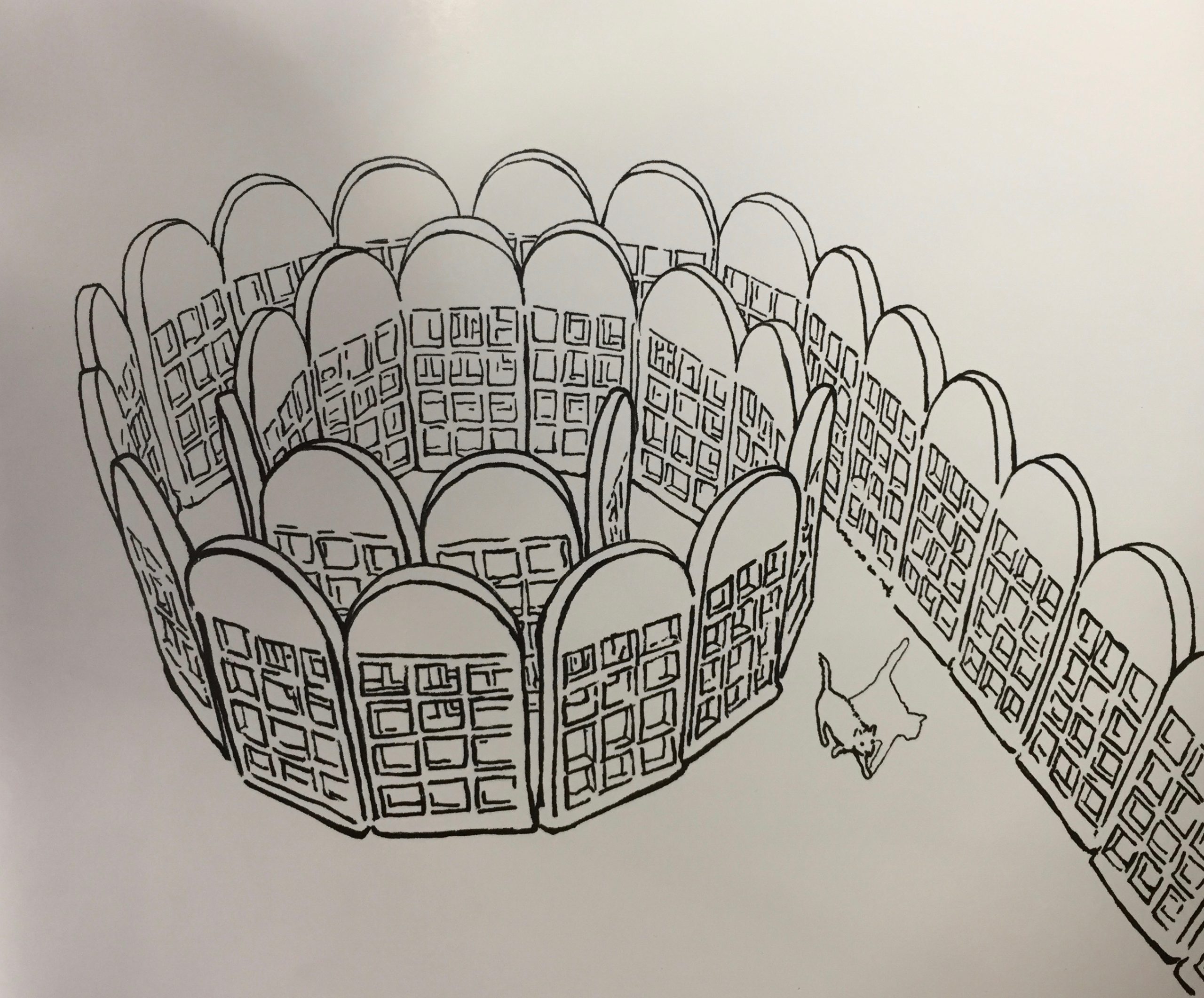

At the castle, you purchase a ticket using Cedis. The price is something like $10, which is nothing considering how far you have come to get here. And considering the price the original ‘visitors’ to the dungeon had to pay. It couldn’t be free when you consider that fact. But the $10 must get stretched pretty far to cover the castle in white paint. Or maybe not. Because as you stand in the courtyard waiting to start your tour you can see the paint is peeling. After you begin your tour and climb the stairs to the outer wall you see the canons rusting. They can’t fire cannonballs anymore. As you walk around the top level, you learn about the history, how the canons failed to protect the castle from multiple overthrows and changes of administration.

You wind up staircases to the captain’s quarters. Perched high in the castle, the windows provide views of the beach to the south and north. To the north, from the window of the captain’s quarters, past the open shutters, you see the Oasis Resort. There’s no glass or screen on the window, just shutters with peeling green paint opening onto long, rugged, picturesque beaches. You take photos of the beach through the window. The contrast of light and shadow lends a depth of perspective. The dark of the room contrasted against the bright sun again highlights the contrast between the slave castle and the beach.

Exiting onto the wall, you linger behind the tour group and take playful photos in the happy sun along the wall, showing off the beach, the impressive height of the castle, and the canons.

The group is going downstairs. In the courtyard there are shadows, and the space isn’t so bright as at the top of the wall, or as the walk to the castle.

Then, you are led into the holding room for the male slaves. There are no windows here. This dungeon routinely housed several hundred captured Africans waiting to be sold into slavery. In your tour-group of 12, you can feel how claustrophobia would creep with even 100 people. 100 is a lot of people to put in one room. The room would be so full that while standing upright, neighbors touched.

An extension cord hangs on the wall to bring power to a light in the rear corner. Without the lamp, even with the door open, you would not be able to see the dungeon you’ve entered. You need light because the floor is uneven and it would be black inside otherwise. But the single light is no match for the physical immensity of the dungeon, to say nothing of the dungeon’s immense darkness. One light isn’t enough for the dungeon. The walls are dark. They seem to eat the light. As does the floor. There could be more lights in the room but maybe it wouldn’t matter.

This dungeon isn’t a place for light. This isn’t a place to see or be seen. The history is still too heavy to let any light in.

The ceiling is high enough to stand, but with a couple of feet of clearance. It smells a like a gym that is too small and hasn’t been cleaned or ventilated. The guide informs you that the floor is now higher than when the room was built because if you were captured, you weren’t allowed to leave until one of two things happed. Either you were chained inside a boat or you died. So this is where you shat. This is where you urinated. This is where you slept, if you could sleep. This is where you threw up from the smells, the claustrophobia, and from other illnesses. This is where you might reasonably have died.

And you have paid $10 to get in, now. You stand with a group of strangers in this place where even the light struggles to escape the fixture whose anachronistic pulse is undetectable. A lamp would flicker, might be eaten alive by scarcity of oxygen. Luckily, the bulb forges on as the breath is sucked out of the room and your lungs and you begin wishing to get back out of this place.

The flash from your camera won’t fight this darkness. It would get lost too. The flash doesn’t have enough drive, fight, or desire to overwhelm the darkness. And you have lost the will to photograph. There is nothing photogenic in a room that won’t crumble, whose floor just keeps building up with excrement.

The curators of Cape Coast Castle manage and maintain it because history can’t be allowed crumble. While Kwame Appiah’s notion that Europe should see the riches of the society it plundered is true, it is also true that Europeans should see the trauma inflicted to commit that plunder. If we are going to learn from history, we cannot ignore the negative spaces.

Sources:

Appiah, Kwame A. “Whose Culture Is It?” Whose Culture?: The Promise of Museums and the Debate over Antiquities. Ed. James B. Cuno. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2009. N. pag. Print.

“Cape Coast Castle &Museum.” Home. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2013. <http://capecoastcastle.ghana-net.net/>.

Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2003. Print.

Rujumba, Karamagi. “At Cape Coast Castle in Ghana, Retracing Slavery’s Steps.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. N.p., 11 July 2009. Web. 16 Oct. 2013.

Sorensen, Colin. “Theme Parks and Time Machines.” The New Museology. Ed. Peter Vergo. London: Reaktion, 1989. 60-73. Print.