Inyoung Seoung’s solo exhibit at The Midway Gallery in San Francisco is titled Heliotropic. That she has presented a twisted forest of trees in a sunny studio might lead viewers to consider that title rather pedestrian. In truth, Seoung is using heliotropic, a term that describes the tendency in plants to grow towards a light source, as a double-entendre. Seoung sees her own work as an investigation of plants that aims to reveal something about humans, so heliotropism is a characteristic of plants and people. For an artist based in Los Angeles, that tendency to grow towards light is obvious, as an LA pedestrian would exist in a consistently sunny American city.

The human tendency to grow towards light can also be vividly seen in the city hosting Heliotropic. During a sunny weekend in San Francisco, city parks such as Dolores, in the Mission district, brim with city-dwellers thirsting for sunlight. Like plants, park visitors reveal their bright plumage in the sunlight. This parallel is something Seoung articulated in an exchange we had about her work: “For this particular series, the tree became the representation/symbol for the human. I saw that ‘trees’ and ‘humans’ were similar. As there are individual humans, there are individual trees that are all different in their own ways (ie. Stems, branches, leaves) but have the same desire in life to ‘grow.’”

The result of Seoung’s investigation is remarkable for what it reveals about humans. While the title and the subject sound bright and while the Midway is certainly well-lit, with skylights pouring gobs of natural light on the massive trees Seoung installed, the heart of her work feels sinister. Seoung is tapping into the unconscious mind as one touchstone of her work: “The lines and branches in my work reflect the trees’ fight and intertwining branches [compete] with one another to reach sunlight, ultimately for their ‘unconscious’ desire to grow. This too represents how we humans interact with individuals in our life while ‘unconsciously’ desiring.” Connections to Freud’s discussions of the unconscious mind are not overt, but the soil seems saturated with references and Freud’s ideologies are often considered twisted.

The association with Freud is one element feeding the sense that there is something sinister at play in Seoung’s work. In viewing Seoung’s language, the sinister is further highlighted through the use of the word “fight” and through the sense that human interaction is predicated on a proto-ulterior motive rooted beyond the conscious mind, a motive that is inaccessible by virtue of being unconscious. Apart from dark associations with Freud, thinking about Seoung’s work drew my mind to Carl Jung and his notion of the “collective unconscious.” Jung premised his notion of the collective unconscious on the belief that shared unconscious thoughts exist among humans in the form of symbolic archetypes.

Recalling the idea of a collective unconscious brought to mind the work of H.P. Lovecraft, a horror fiction writer who tapped into the occult and the primal as a source of terror and anxiety in At the Mountains of Madness: “The touch of evil mystery in these barrier mountains, and in the beckoning sea of opalescent sky glimpsed betwixt their summits, was a highly subtle and attenuated matter not to be explained in literal words. Rather was it an affair of vague psychological symbolism and aesthetic association—a thing mixed up with exotic poetry and paintings, and with archaic myths lurking in shunned and forbidden volumes” (Lovecraft, 41). The fear of the primal is trope that sees humans attempt to distance themselves from a ‘baser’ existence. Flawed or not, the arrival of anxiety in conjunction with the primal or occult persists beyond Lovecraft.

Seoung has stretched Jung’s idea by taking the collective unconscious to a proto-primal, biological level that sees unconscious desires toward ‘growth’ as acting upon people and plants. In following the sun, each attempts to grow, and one sinister aspect of Seoung’s articulation is that neither plants nor humans are aware of exactly what they are aspiring to in their growth. Both threaten to choke out competitors in pursuit of an inarticulable, ethereal goal. Articulated in this manner, interpersonal relationships take on a precarious dynamic as individual growth is pursued ruthlessly but is manifested most profoundly and timelessly through procreative cooperation.

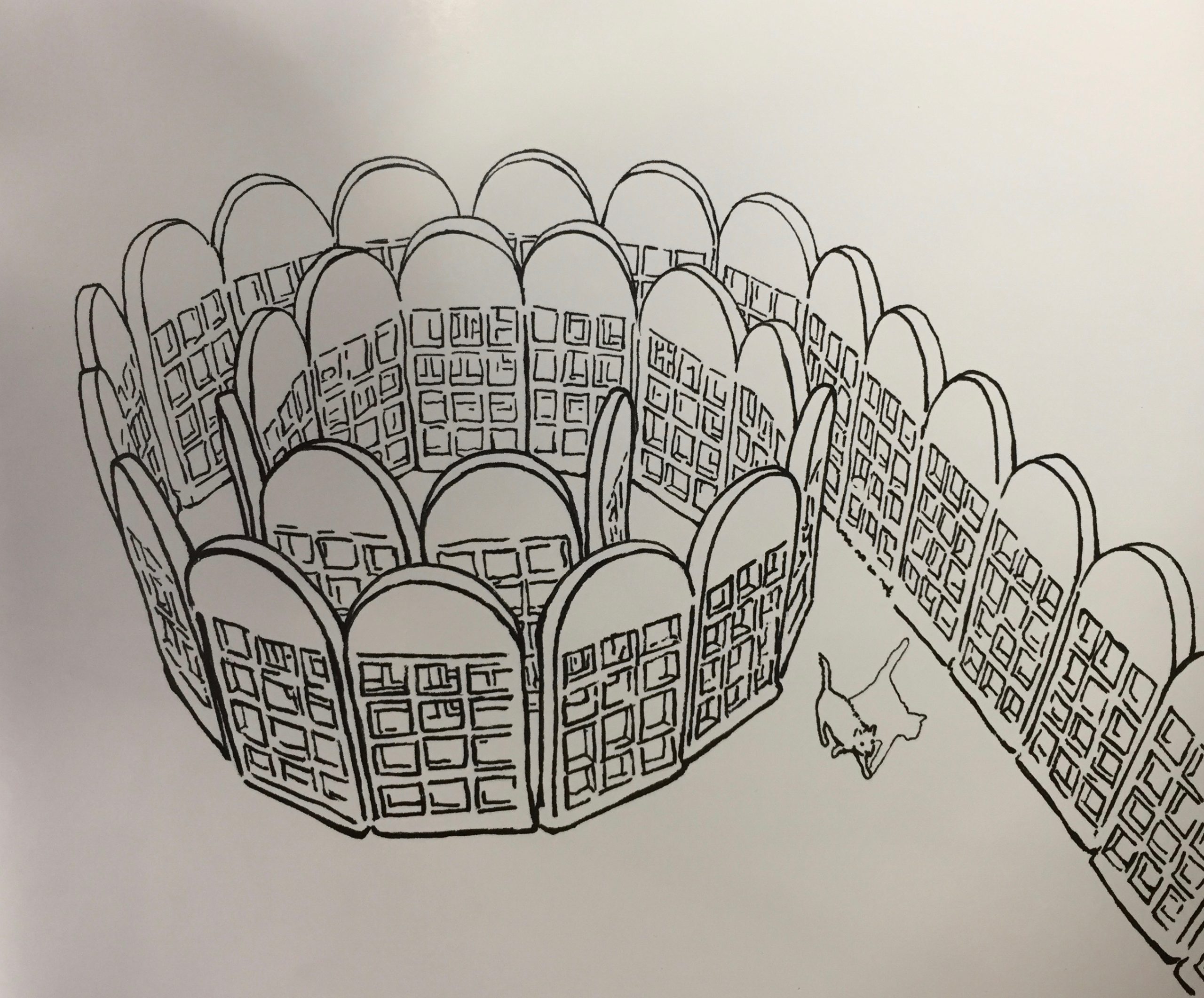

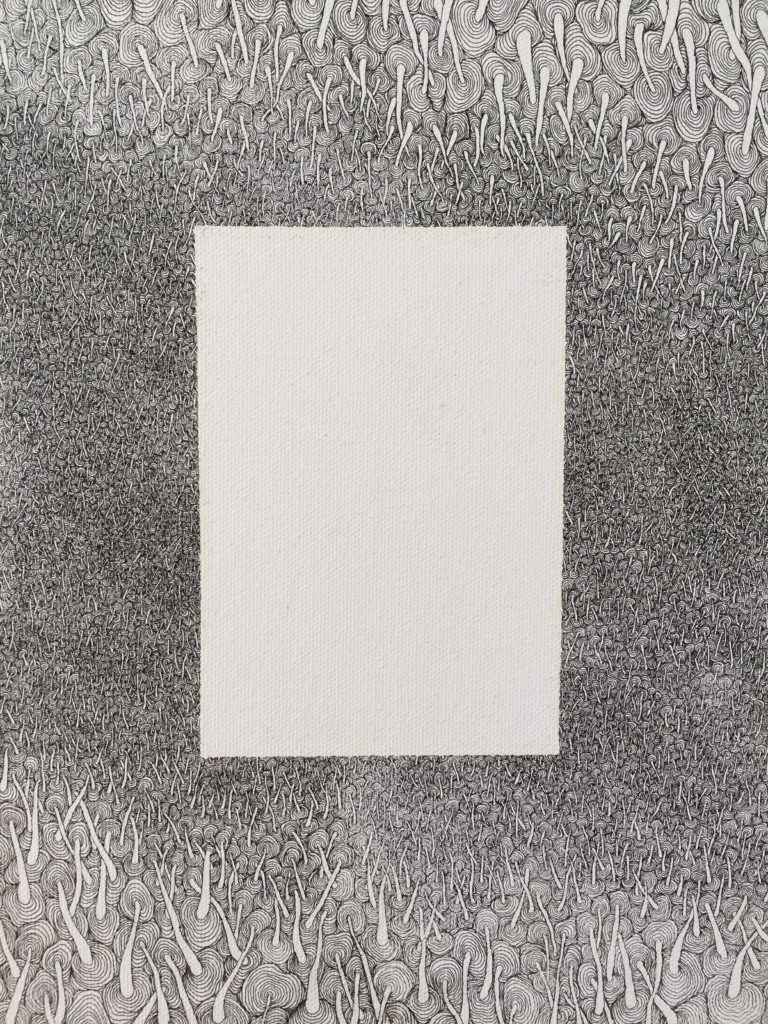

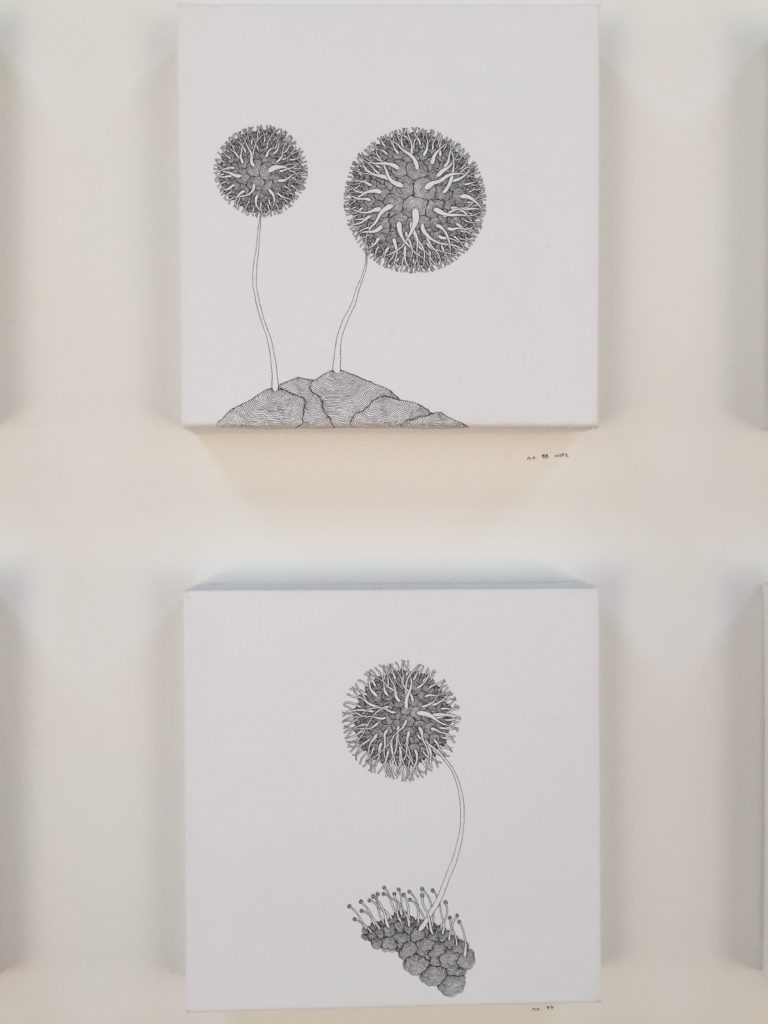

This is where I see Seoung’s art bridging a gap. Seeing her black-ink on white-canvas trees in the context of the black-electrical-tape on white-walls forest she has created, enables viewers to conceive of the macro- and micro-biological aspects of her statement. There are individual 20 foot trees sprawling, wandering up the walls towards Midway’s skylights, while down near the ground are ten-inch, square paintings of mysterious cross-sectional dandelions sitting next to images that could be the Amazon Rainforest viewed from space. Seoung’s forests are so intricate as to be sinister in themselves, for no system could count the infinitesimal lines in Seoung’s densest forest scenes. A robot would be tired from trying to count the lines, and Seoung had to draw each of these fine, tiny lines. The scope of these works is sinister for the way they obscure the individual, operating in the same way as a stereotype.

Looking from a sprawling forest of thousands of indistinguishable trees that could fit in your hands to a tree that covers 20 vertical and 40 horizontal feet is a menacing reminder of the degree to which a generalization can obscure the subject, another point of examination for Seoung: “trees contain endless exclusive patterns that would not show unless we cautiously gaze upon them, close up. Likewise, if we pay more attention to each others uniqueness, it would be easier for us to respect individuals as how they are [sic] than to have stereotypes.” A binary between the individual and the masses is vividly captured.

The menacing binary invading the Midway finds itself balanced by an intrepid whimsicality akin to the sentiment elicited in this passage from Lovecraft:

We were indeed clutched for an instant by a primitive dread almost sharper than the worst of our reasoned fears regarding those others. Then came a flash of anticlimax as the white shape sidled into a lateral archway to our left to join two others of its kind which had summoned it in raucous tones. For it was only a penguin—albeit of a huge, unknown species larger than the greatest of the known king penguins, and monstrous in its combined albinism and virtual eyelessness (85).

The tone of Lovecraft’s fiction is such that everything it touches radiates ominously, but in stepping back from this passage, what the reader is looking at is a giant, blind, and albino penguin. That image could be the punch line of a joke, as there is little objectively threatening about a six-foot, blind, all-white penguin, but in the context it has different valences. When viewed from a certain perspective, Seoung’s black and white trees bring to mind one part black-and-white comic strip, and one part Dr. Seuss-ian landscape. That perspective enables her work to strike whimsical as well as frightening.

Seoung’s paintings toggle from menace to whimsy, and that is crucial to her success. Hers is a recognition that there is something cartoonish about biological species’ unconscious drive to grow individually at the peril of others while simultaneously being forced to reconcile that individualistic drive with the need to procreate via inter-species interaction. Life is cruel and funny. Seoung and Lovecraft both draw on the similarities between humans, other animals, and plants. While both artists ‘paint’ a sinister world, it is in their respective moments of whimsicality that credibility and authenticity arrive in their art.