I

As a teacher, a cup of coffee and a snack in exchange for a few hours of wifi and a table to write a second novel on, is affordable. Renting a doss with an office in San Francisco, is not affordable. Occasionally, I sit down in a coffee shop to write about one thing but something else comes out. My process is a function of my lifestyle.

II

There is a “famous,” introductory cultural studies textbook called Doing Cultural Studies. In the text, Stuart Hall and a team of cultural theorists perform a cultural studies analysis of the Sony Walkman. The purpose is to demonstrate what cultural studies does and to suggest how an interpretation of culture can look. For my purposes, the relevant section of the text examines the possibility that the makers of the Walkman could not have understood how viable their product was (Sony predicted they would sell 5,000 units, but when it was released in 1979, over 50,000 units of the original Walkman were sold in the two months after release).

Evidence of Sony’s expectations not matching reality is built into the hardware of the first Walkman as well; the first generation featured two headphone jacks. There were no ear buds at that time, so only one person could listen to headphones at a time. The thinking was, if someone wanted to ‘privately’ listen to music ‘in public,’ that person was going to listen with a companion. The ‘idea’ that there might be a ‘desire’ for sonic isolation during physical integration had, in a material sense, not been invented.

Sony was initially scared of the seismic possibilities of their idea. They compromised and put two headphone jacks in the Walkman to allow the desire they cultivated of a shared public/private space to feel less alienating. If two people are listening to the same song on a park bench, the ‘private’ listening in public would not feel unnecessarily revolutionary. Even with two headphone jacks, people still chose to listen to the Walkman alone. Incorporating feedback regarding cost and size considerations, the second port was removed in subsequent generations.

Aside from the evidence of a psychically shared timeline wherein people are ready for something that they don’t yet know they want, this historical footnote can be seen as the genesis of an idea that has taken over technology and the world. From iPhones and laptops and tablets to Netflix and streaming music, psychic private spaces are growing as physically private spaces are shrinking. Cities like New York, San Francisco, Seoul, and Los Angeles are extreme examples of this point. Around the world, public becomes the new private.

III

James Baldwin, living in France for a spell, would get his inspiration while eating, drinking, and talking late into the night. Afterwards, he would sit down and write deeper into the night, because that was when real human voices felt the freshest to him and most accessible for use in his fiction.

IV

In 2018, writers can be public and private simultaneously. A lot of creative people operate remotely and as I sit writing in a café, I sometimes think about the creatives around me. I imagine what they’re ‘doing’ with their computers on, their ear buds in, clicking their portable mice with the right hand, all while eating a green tea Bundt cake with the left.

And that is when I have my realization; just as my neighbor tips their green tea bundt cake on its side to eat the icing first.

V

Writers plumb nuance to generate realism in fiction. The oddly specific is often what makes something feel true. I will now pair canonized writers with thematically representative desserts in the hopes that readers feel me.

VI

Marcel Proust — Madeleine

Jack London — Shaved Ice

Emily Dickinson — A Whole Pint of Vanilla Ice Cream, Eaten in Bed

Edgar Allan Poe — Devil’s Food Cake

James Baldwin — Apple Pie

F. Scott Fitzgerald — Flapper Pudding

Henry James — Custard

Henry Miller — Ladyfingers

Willa Cather — Ladyfingers

William Faulkner — Whiskey Cake

Ernest Hemmingway — Flan

Henry David Thoreau — Maple Syrup

Mark Twain — Pop Rocks

Gustave Flaubert — Wedding Cake

Honore dé Balzac — Peanut Brittle

Albert Camus — Meringue

Alexandre Dumas — File Cake

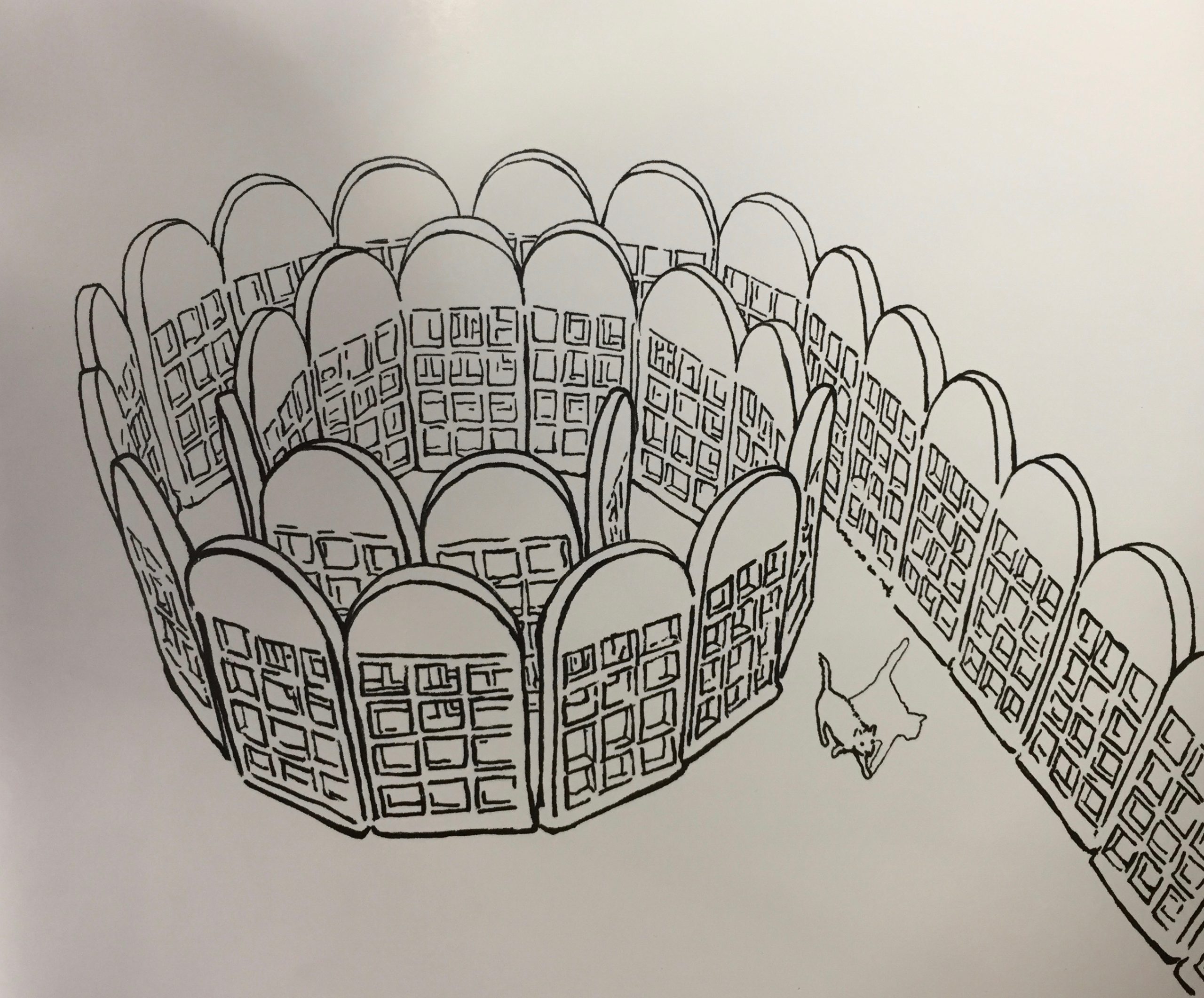

Jules Verne — Croquembouche

Chinua Achebe — Crumble

William Shakespeare — Scone

Charles Dickens — Everlasting Jawbreaker

Emily Bronte — Crème brûlée

George Orwell — Gulab Jamun

Mary Shelley — S’mores

James Joyce — Murphy’s Stout

Lewis Carroll — Crumpets

Rudyard Kipling — Banana Split

Jane Austen — Lemons