The imagery of surfing is tethered to aesthetics. That imagery includes clean white sand beaches, electric blue water, empty lineups, and idyllic barreling waves for the few lucky surfers in the lineup. This essay considers what is behind the appearances surfing maintains and how hard the sport works to maintain them.

Surfing, like gymnastics, is an aesthetic activity. Both activities are called sports and while they require incredible balance and agility, they are largely aesthetic endeavors. As they are aesthetic, both activities require judgment to evaluate, assess, and ultimately decide on a winner (unlike sports that can be objectively judged through timing, as is done in swimming, or goals, as is done in soccer). Surfing shares as much with the visual arts as it does with objective sports, falling at the center of a Venn Diagram of visual arts and objective sports. The question “How did that ‘look’?” carries little value when the purpose is speed or points. ‘Sports’ that require judgment invite scandal and inquiry because different humans judge differently.

In the sport of professional surfing there are two dominant modes, two “career paths”. Those modes are competitive surfing and “free-surfing.” The highest paid “pros” in surfing are the competitive surfers, and while free-surfers can make a living without winning contests, it is harder to make a living. For free-surfers, livelihood hinges largely on the ability to put together video footage or “edits” in order to gain sway over the purchasing habits of viewers who might appreciate particular free-surfer’s styles (or lifestyles) and therefore want to support companies sponsoring favorite free-surfers. Both professional surfing routes are problematic, and there are several high-risk intersections that tend to yield unsightly collisions in the surfing world. The first intersection sits at the corner of aesthetics and objective judgments, the second intersection sees beauty cross poverty, and the final intersection is the corner of nature and progression.

Beauty in the pockets of the beholders

Two high-profile examples come to mind when discussing the intersection of aesthetics and judgment. Before parsing those examples, consider the judging criteria found on the World Surf League website (the WSL is the governing body for the professional competitive surfing circuit). The WSL’s criteria asserts there are five categories analyzed when judging the score of a wave on a scale from 1-10. The five categories are: “commitment and degree of difficulty; innovative and progressive maneuvers; combination of major maneuvers; variety of maneuvers; speed, power and flow.” These five criteria aim to gut, clean, and butcher the aesthetic experience of watching a freeform athletic activity. When analyzing our two examples it will become apparent that these are not comprehensive categories, nor are they exclusive. The first example comes from 2015 when Kelly Slater attempted a maneuver called a ‘backside air reverse’ in competition (for those interested, backside means he is surfing the wave with his back facing the wave, air means he launches himself off of the wave, and a reverse means turning 180 degrees ‘unnaturally’ or ‘in reverse’ before landing). The wave’s scoring caused so much controversy among viewers that Kelly sat down for an interview to break down his wave and acknowledge the ‘correctness’ of the score. Then a head judge was interviewed to explain the score from his perspective.

The way Kelly’s board floats off of his feet, flutters, and nearly flips in the air during the maneuver is unusual, and the fact that he nevertheless landed on his board and managed to do several maneuvers after recovering is absurd. While Kelly claims to agree with head judge Richie Porta that it was an incomplete maneuver and thus not worthy of a higher score, the score of 4.17 Kelly received seemed to be an injustice (as waves are scored from 1 to 10, a 4.17 is on the WSL website’s low end of average). To my mind, Kelly ticked all five of the judging boxes during that ride even if he wasn’t overly fluid. The ‘completion’ component mentioned by Porta, which is not listed on the WSL judging criteria page, was the only ‘criteria’ left unmet.

If the judging criteria and the ‘eye test’ seem to confirm a wave as exciting, difficult, and aesthetically appealing, then it seems the wave was underscored. Such a collision is liable to occur when ‘objectifying’ aesthetics. The second example comes from a contest in France in 2017. On the wave, Gabriel Medina also did an aerial maneuver.

While Medina’s air is admittedly more challenging because he is doing a flip, the 8.57 he received after a single ‘incomplete maneuver’ seemed problematic (8.57 is above the mid-range of the ‘excellent’ subcategory according to the WSL and at the end of the video you can hear them discussing the fact that it was “a bit of a mistake and [Medina] climbed back on…”). This is another collision. This collision inverts the last example but nevertheless collides with semantics and the notion of a ‘complete maneuver.’ It seems that if a surfer ends up on their board and continues surfing it ought to be considered complete, as both surfers did. Compounding the issue is the fact that during the second example, Medina did one maneuver which means he failed to hit at least two of the five judging criteria on his wave (variety of maneuvers and combination of major maneuvers could not have been met). Both surfers seem to have either completed or not completed their rides, because neither rode away cleanly, and given that Medina hit at most 3 of 5 criteria, we have arrived back at the fact that objectivity and aesthetics don’t meld. Judges granted a near-perfect score for doing 60% of the criteria. If competitive surfing’s ideal is to have aesthetically appealing waves surfed by the best surfers in the world, then do the semantics of ‘completion’ have a place in the judging? Does ‘landing’ something “cleanly” make it innately more beautiful? The discrepancy between these scores demonstrates the type of collision that “objectively” judging aesthetics yields. That both maneuvers were amazing spectacles is irrefutable for the dexterity required to not only fly through the air using one’s legs, a wave, and a board, but also to spin/flip and have the corporal awareness to stay on ones board through it all.

Competitive surfing isn’t preoccupied with judging aesthetics and it isn’t the same ‘sport’ as free-surfing. Competitive surfing requires a law degree, experience arguing semantics, and lots of sponsorship money. Competitive surfing doesn’t fret over petty concerns with ultimate truth or intrinsic beauty, because competitive surfing is too busy making sure Medina wins that contests so that the WSL can drum up interest by having the championship come down to the final contest thereby emboldening the narrative that John John vs Medina is the future of surfing. Really the WSL is about profit. Giving judges “time to watch the replay” may just be an excuse to grant the WSL leaders time to tell the judges what scores are in the best interest of corporate sponsors. Should we get rid of competitive surfing? That question is irrelevant because there’s too much money at stake. Besides, watching contests allows viewers to see the world’s best surfers occasionally fall or stumble which may be more valuable than seeing them ride away from nearly every maneuver as they do, impossibly, for the bulk of every surf film. Falling is the most honest part of professional surf contests.

Beauty as poverty repurposed

Surfing’s second high-traffic, collision-heavy intersection sits at the corner of aesthetics and poverty. Surf films are the background for this intersection. When filming for a surf movie, crowds are suboptimal because having a videographer stand on the beach all day filming costs money. The ideal is to have a videographer at one site for a few sessions as the sponsored surfers catch all the waves instead of having videographers watch as their surfers get one wave every 15-30 minutes at a crowded surf break. Surfers can also ride more freely knowing that if they try something difficult on the best section of a wave and fall during the attempt they can paddle back out and catch the next good wave instead of waiting in a queue behind other capable surfers. One result of this ideal is the reality that many surf films budget trips to seldom-surfed, un-crowded destinations. Countries with the fewest local surfers tend to be poor countries because citizens tend to lack disposable income. When citizens are busy trying to feed themselves they probably aren’t buying surfboards and learning to use them.

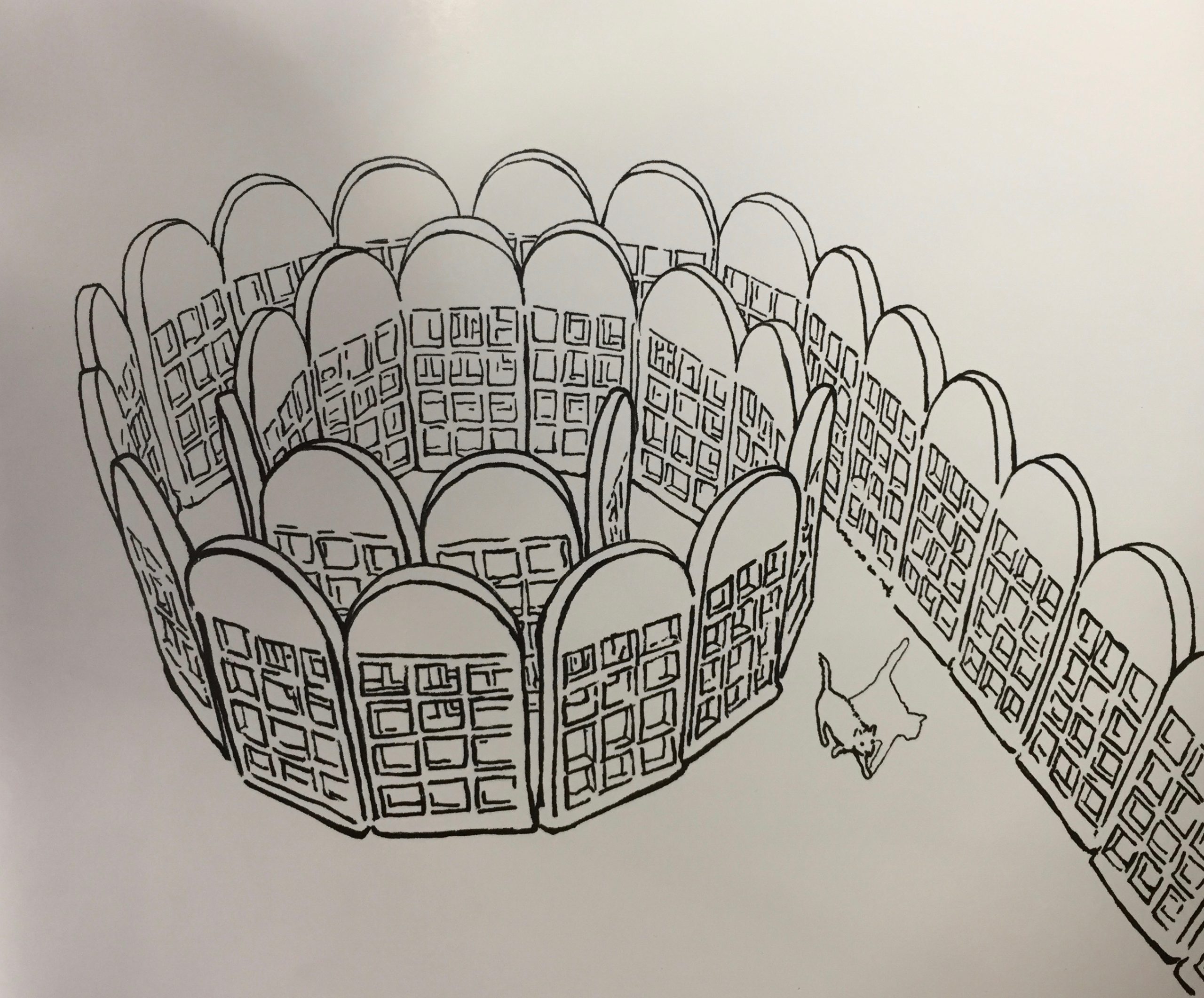

Surf films tend to adhere to one format. That format is: Super-cut of all the surfers that will be in the film surfing a couple waves and doing unbelievable things on them; opening credits; ‘individual sections’ where featured surfers are showcased; a blooper reel before, after, or during the closing credits. Sprinkled throughout surf videos are establishing shots or ‘lifestyle’ shots that give the waves some anonymous context (nobody wants to give up the exact location of a secret break). Because surfers often travel to countries with high poverty rates, establishing shots frequently feature poverty. That doesn’t threaten the aesthetic appeal of a surf video because the right camera filter and special effects can make any barrio aesthetically appealing.

Within the surfing industry, Taylor Steele is one of the most influential and best-known surf film purveyors and has been making films for over 20 years. Steele is a trendsetter in the industry and while he did not invent the trope of filming poverty as establishing shot for a surf sequence, Steele’s 2006 film “Sipping Jetstreams” dwells in the space around the beautiful waves that it sets out to film. I want to spend a bit of time thinking about “Sipping Jetstreams” as a way to consider what it means for surfing to habitually attempt to beautify impoverished places.

The emphasis is on travel in Sipping Jetstreams, as the title suggests, which connects to the pursuit of exotic waves and therefore to surfing. With so many of the destinations appearing destitute, the fact that surfing is a sport of privilege becomes accidentally foregrounded. Nearly every surfer in this video is white, an exception being Kalani Robb who is of Asian decent who through a conspicuous coincidence is surfing in and walking the streets of Hong Kong. The trope in surf films of filming white surfers in poor foreign countries populated by brown faces is a twisted voyeurism that obscures the problematics of the reality.

At the 1:18 mark in Sipping Jetstreams there is an image of two men standing in front of a crumbling brick and rock facade that obscures a dwelling carved into a hillside as smoke billows from somewhere within. Then there is an emaciated donkey. Then there is a surfer dropping into a barrel. The juxtaposition implies a lot. The immediacy of the establishing shot implies that the hillside overlooks the surf break. The music chosen for this segment begs viewers to assume it is Moroccan and further smoothes the visual juxtapositions. The imagery of the building deteriorating, possibly from some sort of conflict, and the deteriorating donkey followed by the musical shift that accompanies the surfer’s ‘drop’ into the wave suggests that the physical space of the coastline and the wave itself are ‘battlegrounds.’ While surfing may be dangerous, the chosen recreational danger of surfing shouldn’t be paralleled with the dangers of poverty. Unless there is a laugh track. This surf film could just as easily be a Saturday Night Live sketch. Satire is most ripe when something has been steeped in its own ethos so fully that the thing believes itself beyond reproach despite rational criticisms being levied.

But Steele’s film seems to take itself seriously. Around the 2:20 mark, we have one of the men who was standing in front of the stone home smoking a cigarette, which confirms the thinking that Steele sees these as parallel worlds of risk. While smoking a cigarette may be a risky choice just like surfing a wave that breaks in shallow water is a choice, living in America with hospitals and the infrastructure to reach them easily is much different from living on a barren coastline off of a dirt road in Morocco without a hospital in sight. Choice doesn’t play much of a role for the Moroccans in the film. Steele seems to misrepresent this intersection so grotesquely that if this were a satire he wouldn’t have to edit the film beyond casting Fred Armisen as the man smoking the cigarette. Imagine Armisen taking a puff of the cigarette, turning to the camera and breaking the fourth wall by saying “people always harassed me about the dangers of smoking… until they saw a Taylor Steele movie.” The cigarette is a trivial danger in this context, which makes imagining someone cigarette shaming a Moroccan who lives in a deteriorating cave that probably lacks electricity, running water, and proper ventilation, comedy gold.

Nodding to poor locals in surf films doesn’t make the act of jet-setting to impoverished destinations on the dime of a sponsor to participate in the glorification of European rape, theft, and imperialism a noble act. The sordid pomp of this surf film trope cherry-picked one of the last vestiges Hawaiian culture, a culture that has nearly been wiped from the planet thanks to globalization and imperialism, and shows that artifact off to other ‘poor’ cultures as though surfing belonged to Europeans in the first place.

The reality is that surfing was ‘discovered’ by white sailors in the 1700’s when they witnessed Polynesians riding boards carved from wood in the surf. ‘Discovery’ translates to Polynesians creating a pastime that was eventually seen by white people. The ‘discovery’ of surfing works the same way the ‘discovery’ of America by Columbus did, which is in direct contradiction with the fact that populations of Native Americans already lived here. These ‘discoveries’ by Europeans represent failures of language. Further problematizing things is the fact that Hawaii, one of surfing’s homes, had white Christian Missionaries ban surfing for religious reasons, which emphasizes the fact that the sport was neither created by ‘western’ efforts nor did they initially broaden the sport’s reach. After the ban was lifted, the sport’s resurgence eventually included a mainstreaming of the sport. Surfing in the United States today is as popular as it is homogenous. Multiple factors, gentrification being one example, pushed dark-skinned populations away from the coastline and the surf in America. Without access to waves it is difficult to develop wave-riding acumen.

Now, economically privileged professional surfers are paid to fly abroad, have their exploits filmed, and those paid vacations therefore become triply exploitative. First, there is the footage of locals that lends color and pacing to films. Second, there is the inherent exploitation of a classist system in America that sees the wealthy living near the coast with access to waves. Third, there are the exploitative labor practices within the filmed countries that produce the name-brand, petroleum-based surf equipment sold to viewers of the surf films.

Progression’s casualties

The final nasty intersection to investigate manifests when the natural world of waves intersects with progression. While Hawaiians performed rituals to honor a koa tree they cut down to use as a surfboard, the sport has again fallen afoul of its origins. Today, the majority of surfboards and equipment are petroleum-based. Surfboards are now made of non-renewable fossil fuels, and to ensure that boards are light for enhanced ‘performance’ the durability of those oil-based boards is willingly sacrificed. Resulting from the desire for high performance and the necessary sacrifice of weight and durability, many surfers go through multiple boards each year while the broken pieces of old surfboards are thrown away. Through the use of fossil fuels for boards, leashes, wetsuits, and apparel, surfers are destroying the environment they would seem to relish. The plastic gyre in the Pacific Ocean is a testament to the waste that humans produce, and surfers tend to ignore the contributions they make to environmental degradation as though those contributions were floating offshore and out of sight rather than flowing all around them.

If the electric blue water and white sand beaches that form the backbone of surfing’s aesthetic are to be preserved, it is critical that surfers get in touch with what it means to coexist with their habitat as the sport implies. Appreciating and interacting with nature should mean a willingness to care for nature, but this is another way the appearance of surfing fails to align with the reality of the sport. The willful ignorance that allows surfers to ride for companies that use sweatshop labor from offshore factories to produce the environmentally damaging clothes they wear also has surfers riding boards that negatively impact the environments that they immerse themselves in. Surfing must begin to realign the inconsistencies and schizophrenias of ‘surf culture’ or the beautiful destinations will dry up.

In John John Florence’s 2015 film View from a Blue Moon, a quote precedes the filmed poverty trope which establishes a segment on South Africa: “We’ve been going to South Africa as a family since we were little. The empty right pointbreaks are a big draw, but our time with the local people is what stays with us.” If John, his fellow professional surfers, and all of us who care about riding waves truly care about the local people and places featured in surf films and care about our home breaks, we need to consider how our voices and purchasing habits could positively impact the surf industry, our oceans, and our globe.

Great Article! Love the video additions