If you missed part one, click HERE

“I remember you was conflicted

misusing your influence

sometimes I did the same”

Track 5 (“These Walls”). Artists take continuity of theme seriously, and that enables them to make individual songs that cohere. An artist that coheres, or a producer that coheres, is often able to connect with an audience, thereby enabling them to have long-lasting, lucrative careers. Emphasizing coherence also enables individual songs make sense as parts of an album, which is a larger ‘single’ artistic unit. The most successful artists create songs that work on multiple registers wherein individual, ‘radio-friendly,’ tracks can be situated alongside the other tracks on an album and retain their meaning while new understanding is enabled by the re-constitution that happens when the album is taken as a whole (sometimes that effort fails, which leads to one-hit wonders, or albums in an artist’s oeuvre that are less popular or feel incoherent).

On track four of good kid m.A.A.d. city, “The Art of Peer Pressure,” Kendrick Lamar says he is: “bumpin’ Jeezy first album.” So I want to talk about Young Jeezy. Jeezy’s albums feel coherent. How do they achieve that coherence? Via continuity of theme. Jeezy talks about trapping and Jeezy’s production inevitably has the rat-tat-tat drum-machine line that has come to exemplify “trap music.”

Whether discussing drug dealing, how not to get caught dealing, or discussing being locked up, there is a unity to the ethos Young Jeezy creates. To Jeezy, those things are all, supposedly, part of the trap lifestyle. To his audience, the ethos Jeezy creates is taken as somehow authentic or representative of a particular lifestyle (that lifestyle is so foreign to most of his listeners that they couldn’t question the authenticity if they wanted to). The so-called ‘trap’ lifestyle is often discussed in hip-hop and is a localized extension of the ‘thug’ trope found in much rap. It is easy for an audience familiar with gangster rap to visualize a painting or comic strip about “trapping” using the details from Jeezy’s tracks. Jeezy does not appear as a man of contradiction and his confidence and bravado leave listeners with the sense that his vision is real.

Another stamp of legitimacy is lent to Jeezy’s work when he has other rappers featured in guest spots on his album. The trap-esque gangsta rappers he features on Let’s Get It: Thug Motivation 101 act as citations validating the veracity of his ethos. That veracity is crucial, because Jeezy doesn’t always offer a monolithic front that is free of contradiction.

On “Don’t Get Caught,” Jeezy raps about how being polite to a cop is a good idea. Yet, listeners don’t consider Jeezy contradictory or paradoxical or conflicted. Why? He has offered himself and other rappers as his verification of identification. And he is complying with police under specific circumstances and in specific ways. Since Jeezy wants to stay a trapper and not become an inmate, he shouldn’t engender the ill will of a police officer (especially since he has a trunk full of drugs and guns and the smoke from his blunt is still clearing out of his car). So Jeezy endorses compliance with police, especially when you are lying to them to hide your nefarious dealings. It is a complicated explanation, but his confidence and credentials make it possible to sing along with the track without giving a second thought to the complicated-possibly sacrilegious against the ‘never talk to police’ hip-hop-stance.

Jeezy’s persona has similarities to another rapper who Kendrick Lamar has collaborated with, called Pusha T. Jeezy and Pusha T both talk about dealing drugs and have fantastic exclamations that they employ during their songs. Jeezy says ‘yeaaaaah’ and Pusha T says ‘yeeeuck.’ While jeezy is celebrating his past and present, Pusha T is disgusted by his past and seems conflicted in his present. Clipse, the group formed by Pusha T and his brother Malice, feels unsettled about the group’s drug dealing past: “It shames me to no end to feed poison to those who could very well be my kin…” In spite of his ambivalence, though, Pusha T raps primarily about the luxuries of a drug dealing lifestyle.

Jeezy raps in a jubilant tone that seems appropriate for his celebration of the drug-dealing lifestyle. Pusha T, in a stylistic contrast, raps in a manner triangulated amid three emotive sentiments, disgust, somberness, and maliciousness, while nevertheless celebrating drug-dealing lifestyle luxuries. That is Pusha T’s contradiction, the one that balances itself against Jeezy’s contradictory stance regarding police cooperation. Pusha T suggests drug dealing is reprehensible while celebrating the lifestyle that drug-dealing apparently affords. Both artists occasionally offer contradictory fronts yet neither artist is received as generally complicated, contradictory, or conflicted characters.

The continuity of these artists and their albums comes from thematic choices. Thematic choices arise, supposedly, out of life experiences. Jeezy and Push are theoretically putting their lives on display. Rapping about life is the institutional standard, and in an effort at streamlining their music, Jeezy and Pusha streamlined their lives. They cherry-pick the topics they want to discuss and those topics are almost exclusively drug-related. The precedent of gangsta rap’s treatment of a metaphoric ‘drug dealing’ is also a feature of the hip-hop institution. This metaphor configures selling albums as simply selling a ‘fix’ to people. Consumers are conceived of as addicts or ‘music-junkies.’ Pusha, as evidenced by his nom-de-plume, may be ‘dealing’ more heavily in a classical hip-hop ‘selling rap music is like selling crack’ metaphor than Jeezy, but both adhere to their themes because the coherent façade those themes provide is what listeners expect, and neither artist wishes to upset that coherent reading. There is, after all, great monetary value in each artist maintaining his respective persona.

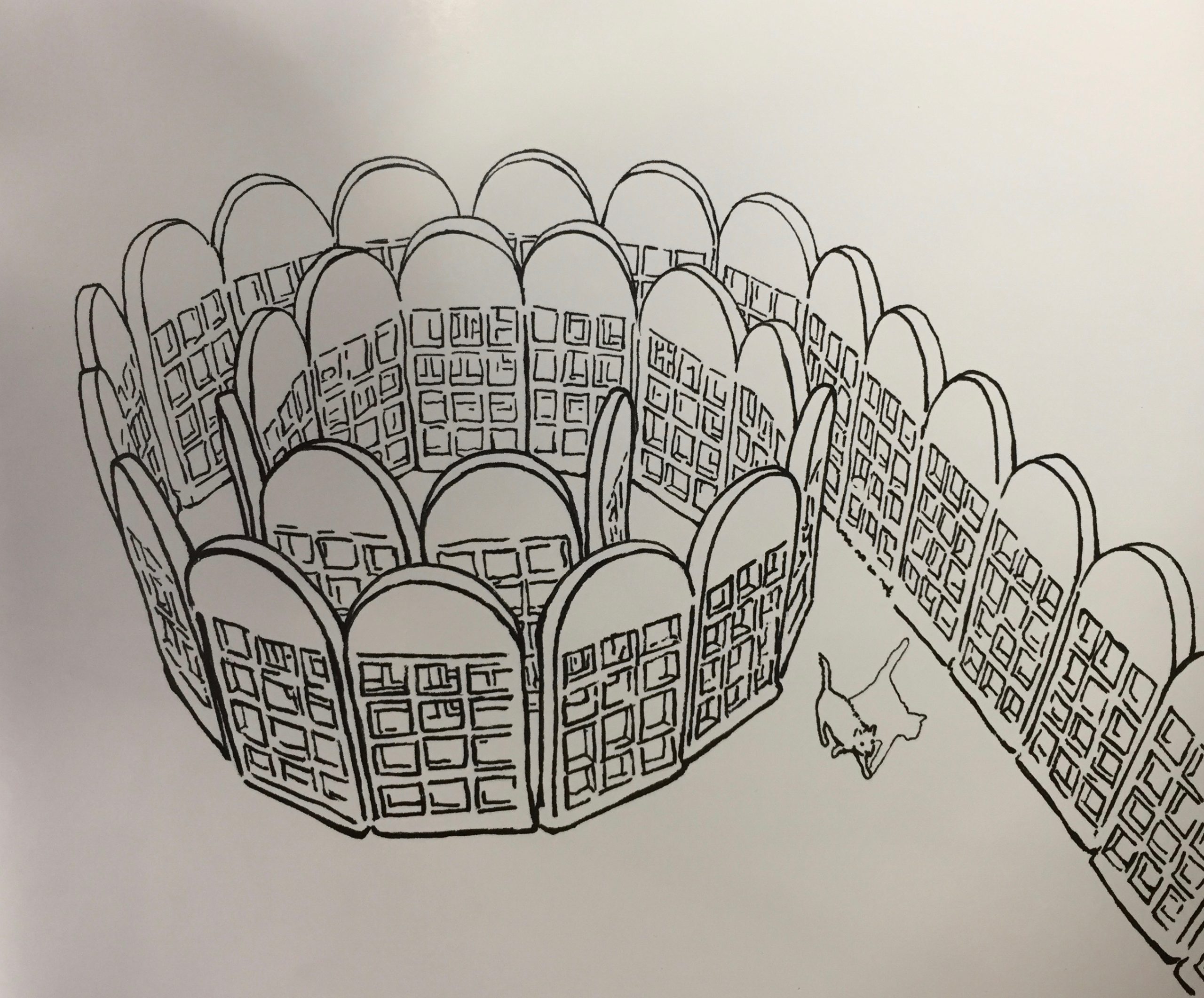

Having pigeonholed their personae, whether by choice or circumstance, each artist must now live with the pressure of trying to live up to the lifestyles they sell. These self-inflicted expectations can only be met if these artists continue to exploit their cultivated personalities, leaving each with few thematic options when recording new albums. Their unity of theme became a singularity of expression. There is little room left for artistry in the work of these two artists. The walls of the institution, partially of their own making, have delimited their expression. ‘These walls’ are talking, telling these artists to toe the line.

The institution polices itself and it, like all enforcers, is best equipped to handle cases that it has seen before. Pusha T and Young Jeezy can be managed more easily because of their similarity to others who have come before them. The personal histories of these two fit a hop-hop mold, which facilitates their cultural salience while also limiting their potential for political impact. Each new hip-hop artist must first establish their personality, which generally hinges on their creation of a personal history. When that history aligns with hip-hop predecessors, it is easily commercialized as the public’s palate has already been attuned to it and they can be placated by more of the similar. That placating is not the same as being satiated. It is the search for something substantive that leads listeners to continue searching for ‘new’ artists. In that search, artists who achieve a ‘new’ sound or who break away from the classical mode often develop large followings.

Drake, in talking about his personal history, achieved a ‘new’ sound. Drake’s life is not a hip-hop storybook because Drake grew up fairly wealthy as a Jewish kid from Toronto Canada. He also, famously, grew up acting on the TV show Degrassi. Drake’s literal, temporal ‘self,’ is one subject he discusses and because his is an unusual trajectory within hip-hop it sounds ‘new,’ but Drake’s real hip-hop innovation is his willingness to be emotional, thereby becoming an emotive character. Drake can conjure the usual anger or lust or elation that is found in much hip-hop, but what he does more than most rappers is draw listeners into angst, depression, heartbreak, and self-consciousness. His unity of theme really comes from his emotionality.

Drake is dealing in a distinct set of emotions, a set that is separate from the usual braggadocio and extreme self-confidence, and he has become successful because emotion is timeless. While that emotionality may be off-putting, it is also proving to be a relatable and profitable topic. Listeners understand emotionality, even if hearing it in rap is unusual. Listeners comprehend sadness and self-deprecation. Drake seems to be pulling the Blues of R&B back into the fold of hip-hop. The timeline would say R&B came first, but because Drake calls himself a rapper first I think he probably sees himself as bringing blues back to hip-hop, if he makes these decisions consciously.

Beyond simply being bluesy and having listeners who appreciate that, Drake’s listeners also probably understand hiding behind a façade of cool to pretend those emotions aren’t real. That is also something Drake does in his music. Drake will be emotional, but will also embrace the braggadocio that represents the institution of hip-hop. Drake is emotional and his emotions are bi-polar. Because of that, he often makes ‘songs’ that are two songs. Listeners understand feeling multiple emotions ‘at once,’ or in one song. Drake will use two beats to divide songs in half. Often one half of these songs is audacious bragging while the other half stumbles back into self-pity or despair over a girl who has left or mistreated him. Drake cares about his statement and cares that listeners care, and he cares to show his contradiction.

But Drake’s ‘contradictions’ are most commonplace, and are comfortably encompassed by a single façade. The contradictions of his character are simple, faux-contradictions that are easily comprehended. For anyone who has seen MTV dating shows like Next, it makes sense that when a date with a person is desired, if the object of that desired date rejects the desire-r, that desire can quickly turn to spite. On Next, that spite was seen when ‘losers’ would tell the camera all the reasons that the ‘next-er’ was foolish for not picking them, a flourish that generally ended with the person who was next-ed ‘admitting’ that they actually weren’t that interested in the other person anyway. This is the sort of contradiction that Drake exhibits. The commonplace triviality of such swings of emotion and confidence make them relatable and ultimately, under the right circumstances of beat and rhythm, catchy.

On the song “Furthest Thing,” Drake’s bipolar work can be seen at its contradictory peak. In part one of this two-part track, he is trying to get back together with a woman who has apparently moved on from him: “I can’t help it, I can’t help it, I was young and I was selfish I made every woman feel like she was mine and no one elses and now you hate me…” So while Drake is crooning to this woman and wishing to get her back, his contradiction comes to light. He was bedding multiple women and doing it so effectively that they would fall for him. Drake’s prowess and ease with women is thus, contradictorily, his burden. The woman he really wanted to be with long-term wouldn’t put up with his antics and moved on, so now Drake is pining for her. Wanting what one can’t have is relatable. Drake embeds his personal failings in layers of carnal success.

On the second part of “Furthest Thing,” the first part of the ‘first’ verse (that is, the first verse that comes after the beat changes to introduce part two of the song) sees Drake living it up, but by the end of the same verse he is criticizing others for partying too much: “Naked women swimmin’, that’s just how I’m livin… Y’all niggas party too much, man, I just chill and record.” Drake represents a contradiction people can understand and envy. Life just comes too easy to him. Drake’s sexual/emotional prowess is so profound as to be unenviable, otherworldly, or super-human, which verges on making him un-relatable for being flawless and thus inhuman. In spit of all that, he remains relatable because he is unsatisfied for failing to get the things he wants most (usually a woman). Drake is, for hip-hop, the right kinds of emotional and he articulates his contradiction in flowery spun-cobweb language that obscures the reality of its childishness. Drake works, as an artist, largely because he has no stake in elevating consciousness. He has no stake in social welfare. Drake sells emotional confusion, complicating the emotionality of listeners by offering a bizarre lens through which to view sexual mores while never actually commenting on how those mores might be flawed or on how morally bankrupt his music is. Drake never aims above the heads of his listeners. He simply shoots for the heart.

“I remember you was conflicted

misusing your influence

sometimes I did the same

abusing my power, full of resentment

resentment that turned into a deep depression

found myself screaming in a hotel room

(aaaaaaahhhhhh)”

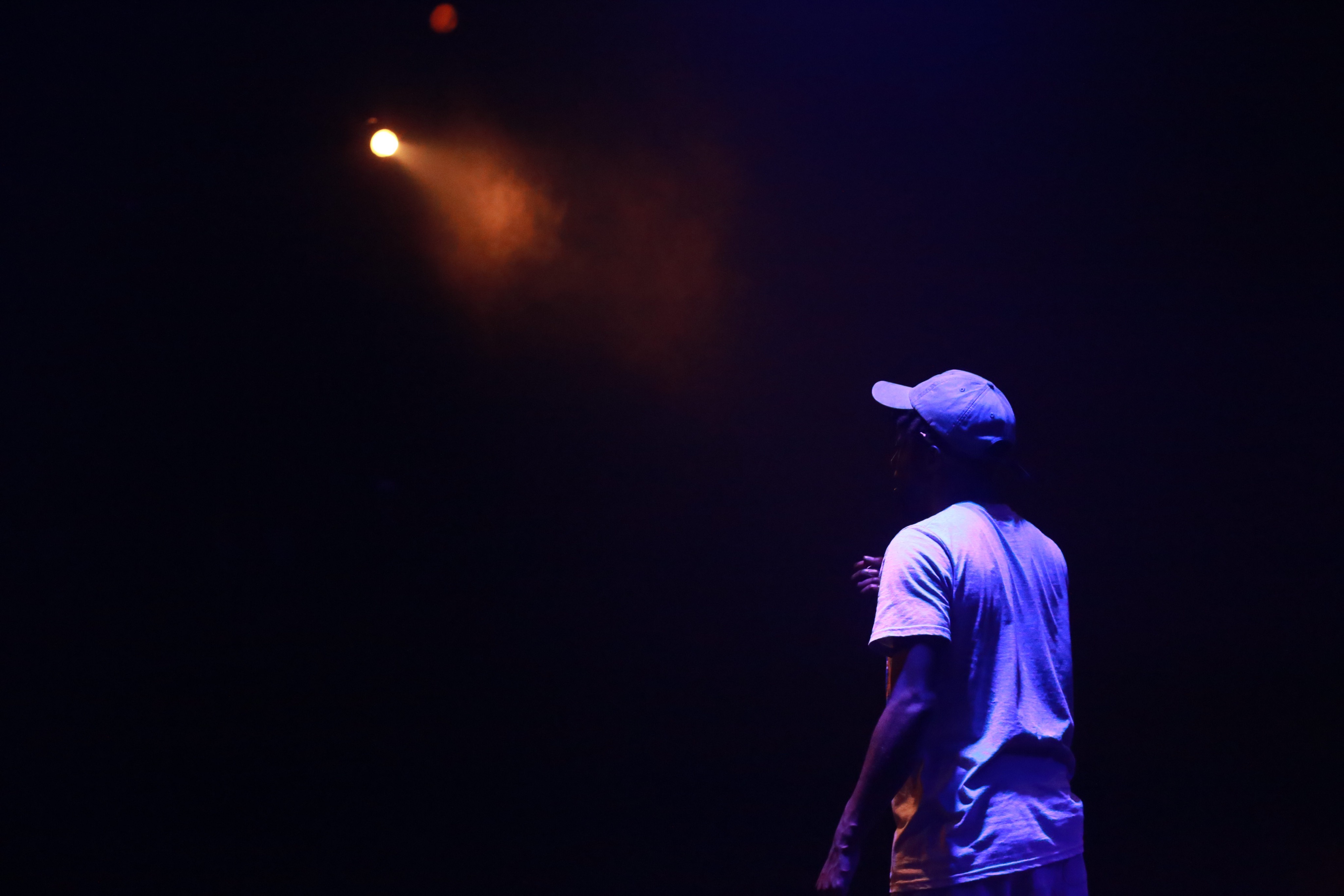

Track 6, (“u”). No song reveals as much about Lamar’s wrestling on this album as “u.” It’s the sixth song on the album. Before hearing “u,” I sent that giddy text to my friend calling this possibly the best album ever. As “u” wound on, I was feeling another emotion. I needed water. Not because I was thirsty.

…in the middle of saying something so important that I need to keep talking before I lose it but I’m starting to cry and can’t lose my momentum and I need water to wash this big, hearty, painful apple core out of my mouth or I won’t ever get this out, just some water pleaseeee

The counterweight to “i,” I suppose Kendrick is right: “loving ‘u’ is complicated.” If “King Kunta” is cryptic, “u” is abstruse. No song in Lamar’s oeuvre brings the question of who is speaking and who is spoken to further to the fore. From the title alone, the question of perspective is made central. Why did Lamar choose not to capitalize “u” or “i”? What does that choice mean for the perspectives offered by the many voices on “u”? Any specificity in these pronouns is undermined and listeners are alerted to the fact that the interpolation of the album is on the upswing. I don’t believe consideration of voice and perspective could be brought more to the fore.

Because of the title, “u,” and because the tears it conjures are the closest and furthest a thing could be. Tears are the most fore. If your perspective is anchored to your eyes and your vision and what you perceive with those eyes, the water that fills them is about as distinctly ‘fore’ that something can get. And yet those tears blur vision, thereby disabling the perceiver’s ability to clearly perceive. You have these eyes, and you don’t really like when things get in them. And you rarely cover them, except with sunglasses, which are supposed to make it easier to see. You only really like when your own eyelids touch your eyes. That’s a short list. Tears are probably the things that fill and cover your eyes second most in your life. When they come, they cause swirls, they are right in front of your face. And you put them there. They are like when you look at a chilled bottle of liquor and can see eddies in it, the swirls blurring your vision. In alcohol, the eddies are like little clues to the murkiness you are inviting with each sip.

In your eyes, when tears form eddies between your vision and the world, what they foretell becomes unclear, but the proximity channels a higher degree of intensity.

The song offers verbal lacerations: “I place blame on you still, place shame on you still.” Who is “I” and who is “you”? What is “I” blaming them for and why should they feel shame?

“What can I blame you for? Nigga I can name several-situations I start with your little sister baking-a baby inside, just a teenager… Where was the influence you speak of? You preached to 100,000 but never reached ’em, I’ll fuckin’ tell you-you fuckin’ failure… the world don’t need you!” is Lamar talking to himself? Like a writer of fictions, the author can’t be assumed to be the narrator and can’t be assumed to be the speaker. So who is I? Is Lamar talking to his genre? Is this “little sister” a real person or an exemplary metaphor like the teenage Brenda from Tupac’s “Brenda’s Got a Baby”? Why do all these impersonal pronouns make it all so much more personal? “Thought money would change you-made you more complacent…” that you makes it personal to me and personal to this voice that I know is attached to Kendrick Lamar, who has money now and I wonder if he has been accused of changing or being irresponsible? but he is the most responsible artist I can think of-I take it personally when I hear him hypothetically maybe talking shit about himself from the perspective of I don’t know who. And the “you” and the “I” and now I’m so involved that I don’t even have a sister but I’m feeling awful for letting something happen to her when I was supposed to be watching out for her. This noisy back-and-forth and then, scrrrrrrrrrttttttt

That “scrrrrrrrtttttt” represents the track’s eventual interruption by the drunkest sounds ever referred to as “music.” The track’s interruption struggles to re-establish coherence around a Spanish-speaking maid knocking on the door of a hotel room: “Housekeeping. Housekeeping. Abré la puerta… no hay mucho tiempo…” The production is a languid lament featuring a trumpet loping along in the background as the refrain “Loving you is complicated” is repeated by a female voice, chopped and looped severely, but not so severely that listeners are unable to comprehend the disjointed sentiment that “Loving you is complicated.”

And as the pieces of the shattered image reverse-break back into place, “u” and its 100-proof love are sitting alone in a hotel room: “you ain’t no brother, you ain’t no disciple, you ain’t no friend. A friend never leave Compton for profit, or leave his best friend little brother-you promised you watch him-before they shot him. Where was your antennas? On the road, bottles and bitches… third surgery they couldn’t stop the bleeding for real. Then he died. God himself would say you fuckin’ failed. You ain’t try… [mumbled blend of “lovin you is complicated” as the horn laments]… I know your secrets nigga, mood swings is frequent nigga, I know depression is resting on your heart for two reasons nigga…and if this bottle could talk [ice clinks in a glass, as big gulps of liquid are swallowed between lyrics]… I cry myself to sleep, bitch everything is your fault…”

The song is disorienting. It is profound. “I cry myself to sleep”? is this the same “I” who is slanging accusations to the “you” who “ain’t no friend”? if that is the case, then the “you” should be crying themselves to sleep. But maybe the speaker takes on dual perspectives, speaking for the failure, while also speaking as the person who was given assurances that weren’t followed through on. And where is Kendrick Lamar in all of this? Is he assumed to be there because of the Compton reference? Or is that assumption unfair? The tangled perspectives again allude to collision, to being “conflicted,” to the “gemini screaming for help” referenced in the song “Hol’ up” from GKMC.

Trying to accurately capture, in writing, all that these lyrics might mean is a difficult task. And maybe that’s the point. Maybe orientation is discarded in order that listeners be stripped down to something approximating raw emotion. Perhaps you are the one who should feel bad. The speaker says “you” often enough that maybe you do start to feel bad. Like a fortuneteller picking up on a glint in your eye and then pushing the buttons on your soul that will challenge you to face fears and acknowledge the emotion that you buried alongside a loved-one. The speaker is pushing buttons until the fortune-your failings-and your tears come to the fore. “u” doesn’t just talk about emotion and feeling conflicted, it lives those things just as it tasks you with living them.

Track 7, (“Alright”)

Just when listeners are thinking “I need a minute,” when emotions are being bent to the verge of breaking, the next track, “Alright” picks up: “Alls my life I hads to fight, Nigga… I’m fucked up, nigga you fucked up, but if God got us then We Gon Be Alright!” Just as listeners are bottoming out, wallowing, screaming in a hotel room “AHHHHHH,” they are reminded that “every little thing is gonna be alright.” “Mood swings is frequent” indeed.

Lamar just finished lamenting: “can’t stop a suicidal weakness” when the triumphant gospel harmonizing of “Alright” begins. The song provides positivity at a critical moment. It isn’t just the energy and the use of the titular adjective that make this song distinct, but again the way Lamar deploys pronouns. From the finger-pointing sadness, depression, and animosity of “u,” the communal “we” of “Alright” is a welcome and beautiful sentiment. The statement of this song resonates for its placement after “u” and for conjuring a sudden unity out of the wreckage of the album’s first three tracks. While the conflicted protagonist of the album appears split into a dual, alienated, Gemini-self, the strength and positive praxis of the album appear when unity is achieved via the pronoun “we” on the song “Alright.” While it would be simplistic to claim that using a pronoun of mutual accountability might solve societal problems, it is nevertheless notable that Lamar is conscious of the power of language and deliberate in acknowledging the power of holding oneself accountable. It is notable because Lamar is not merely challenging listeners and aimlessly critiquing society. Kendrick Lamar is assessing the institution he believes to be flawed and working to repair damages wrought by that flawed system.